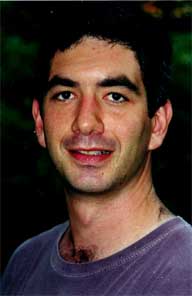

Gabriel Bernstein’s Men of Magic & Mystery

Gabriel Brownstein’s latest book, The Man from Beyond, is a fictional account of the contentious friendship between Sir Arthur Conan Doyle and Harry Houdini. It’s a relationship that’s been explored by other writers over the years, including William Hjortsberg (Nevermore) and Thomas Wheeler (The Arcanum)—in fact, we may hear from Wheeler soon, but that’s another tale to be unpacked another day… Anyway, when The Man From Beyond came to my attention, I decided to ask what the story behind the story was. And this is what I found out…

Joan Didion’s advice to writers about words applies to novelists and their subjects: You don’t choose them; they choose you. Why did I write a novel about Harry Houdini and Arthur Conan Doyle? Why are so many other writers drawn to these subjects? I can’t answer. I can only tell you in my case how it happened.

In a church basement book sale, I saw Houdini’s name in red on the spine of a musty black hardcover. I was surprised to see that he was not the subject, but the author of the book, A Magician Among the Spirits, a title whose power to me was incantatory. At this point in my life, I had published a couple of stories in literary quarterlies, stories that would become part of my collection, The Curious Case of Benjamin Button, Apt. 3W, but I had no notion those stories would be put together in a book. My first child had been born. My first novel had garnered only warm, encouraging rejection letters. Had I been a sane person, I probably would have given up writing altogether. But I opened the cover of Houdini’s book, and there on the frontispiece was a picture of the magician shaking hands with Arthur Conan Doyle. There’s a moment in Othello when Iago says: “It is engendered.” That’s what happened when I saw that photograph. I was going to write the book, even if I did not know it then.

A Magician Among the Spirits tells the story of Houdini’s fight to debunk the Spiritualists and mediums who came to prominence in the 1920s, a fight in which he was opposed not only by Conan Doyle, but also by the editors of Scientific American. The story Houdini told was compelling, but more compelling to me was his prose style. I recently read a biography of Muhammad Ali, and it turns out that Ali, as a schoolboy, woke up before dawn to do roadwork so he could become the heavyweight champion of the world. Houdini, as a boy, hung upside down by his feet so he could pick up sewing needles with his eyelids. Like so many geniuses, he had the gift of mania. And the force of his personality hit me through the book. Like Ali’s, Houdini’s language seemed an extension of his physical genius: indominatible, fearless, and fierce. So the idea for the book grabbed me, but I resisted. It seemed too light a topic, too cinematic, too often done. But resistance proved futile. I found myself working in longhand on the Long Island Railroad on the way out to work.

Sometimes you hear people talk about writers and their books as though the books were the writers’ children, but for me looking back on writing The Man from Beyond is like looking back on an old love affair. Writing a novel is an irrational act, an act of passion and of will in which one tries to take one’s most interior life and make it concrete and real. Houdini and Doyle, in their crazy fights over spirits and Spiritualism, tried to act as if their worlds of entertainment—of magic and of mystery—were rational worlds fit for public debate. They succeeded: Their adventures appeared on the front page of the New York Herald Tribune, running in gray columns between reports about the Russian Revolution and Congressional debates. So why do so many novelists (E.L. Doctorow, Michael Chabon, Caleb Carr, Julian Barnes) write about these men? The answer seems easy to me: Doyle and Houdini are not celebrities, they are heroes, one part history and one part myth, the most basic subjects for stories.

21 November 2005 | guest authors |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.