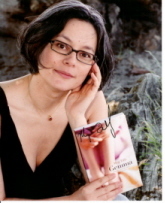

Meg Tilly Recovers Her Voice

I recently interviewed Meg Tilly for GalleyCat about Gemma, her first novel in more than a dozen years. As we were talking, she told me a story about the story’s beginnings that I knew would be of interest to Beatrice readers who are trying to find their own writing voices, so I asked her to email me more of the details so I could present them to you.

People have asked me how I managed to get inside the mind of Hazen Wood, the thirty-six year old pedophile in Gemma. How was I able to make his thought process so realistic, to figure out what his motivations were? They want to know how it felt to write him; was it hard for me, given my background with this type of predator?

The answer is a complex one. Yes, I had an enormous amount of resistance to writing anything from this man’s point of view, let alone a novel where he is one of two principal characters. I don’t think I ever would have voluntarily chosen to spend even fifteen minutes of my adult life in his company.

The Hazen in my book first came into being in 1999. After Singing Songs was published by Dutton in 1994, I became severely blocked. The reaction from my family to the fact that I had not only written, but even worse, published my memories as a child was…to put it lightly…not pleased. When Singing Songs first came out, only one member of my family was speaking to me.

I hadn’t thought it through, realized how violent their rejection of me was going to be. I figured since the rest of the world thought it was fiction, why would they care?

The writing that had once flowed out so happily slammed shut. I staggered around for a couple of years, totally bereft, and then at some schmoozy party, somebody mentioned that they belonged to a writers group and was going into raptures about it. It seemed kind of dumb to me, the idea of sitting in a room with a bunch of people writing. I’d always enjoyed the quiet solitude of diving into the word on my own. But at this point, what did I have to lose? I was writing squat. I promptly joined not one, but two writers groups, both meeting once a week, to try to combat this blockage.

The exercise that brought Hazen about came to me around three years into my groups. We were instructed to write from the voice of the other, someone the polar opposite of oneself. Male, if one was female, and visa versa. Someone whose mind, their way of thinking, you could never imagine understanding. We were to put ourselves into their shoes and write a piece from their point of view, without judgment. Immediately, my stepfather’s face flashed into my mind, followed by my mother’s ex-boyfriend of twelve years who was also a violent man and a pedophile, my step-grandfather who molested me when I was five, and another family member who forced me to perform a sex act when I was seven. Everyone was writing, I could hear their pens scrambling across the page, everyone but me. I sat there paralyzed. Memories of these abusers stealing my air, making my face run hot and cold. I couldn’t write. Just sat there shaking. I wasn’t able to get one word on the page.

Luckily for me, the class ran over and I didn’t have to read my nothing. It was after eleven o’clock at night by the time I got home. I was too agitated to go to bed, so I went into my writing room and tried to write. Finally around two o’clock, something broke, and Hazen’s voice dropped in. He wanted to tell me about the first time he had sex with Gemma. I was shaking when I was done—felt slightly nauseous, coated in him somehow, needed to take a shower.

Gemma’s voice took longer to find. I actually didn’t even know I was looking for it. Just knew that I didn’t, couldn’t make this short story into the novel that my agent, Charlotte Sheedy, was insisting I write. Then one day, Gemma started talking to me and I thought, “Ah… Now I can finally write this book.”

30 October 2006 | guest authors |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.