The Beatrice Interview: Kate Bornstein (1998)

Kate Bornstein burst on the scene a few years ago with Gender Outlaw, a memoir deeply rooted in theory (or, perhaps, a theory book deeply rooted in memoir). “Because it was a first book,” she recalled in a recent telephone conversation. “I was afraid, and I couched things. When people didn’t get the Easter eggs, and I felt confident that it was safe to speak this voice, I just figured, ‘Fuck it.’ I didn’t want to pull any more punches. I was getting labeled as an ‘expert,’ and I didn’t want to be that. I wanted to write an Everything I Always Knew About Gender… kind of book, but then I realized that what gender needs more of is questions, not answers.”

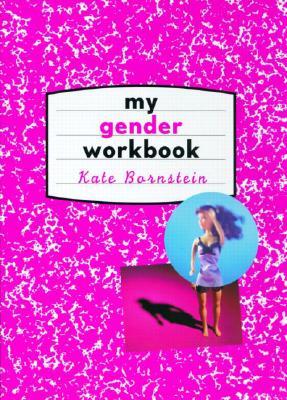

The result is My Gender Workbook, a text which forces the reader to grapple with his or her own ideas about gender at length, challenging cultural assumptions through direct interrogation. Books often get labelled ‘thought-provoking;’ this is the book that lives up to that description. “I don’t want people to think about gender and come to the same conclusions I did,” Bornstein said, “but I do want them to think about gender.”

Bornstein has other projects going on, including a teaching position at Miss Vera’s Finishing School for Boys Who Want to Be Girls, based in New York City. And, having plumbed the depths of gender, she’s taking a leap into new territories: “Right now, I’m exploring sex. Orgasms, breathing, feeling good with my body. I was an active anorexic for 25 years. I hated my body, hated who I was. It wasn’t just because I had a guy’s body, because when I became a woman, I learned how to hate my woman’s body, too. Now I like my body. I feel sexy these days.” With her girlfriend, sexual researcher Barbara Carrellas, Bornstein continues to explore her body and its neverending capacity to surprise her.

What led you to choose the workbook format?

My first art form is performing, not writing, and I’d been doing performance art in reverse. Instead of bringing a static art form onto the stage and performing it live for people, I’d been bringing my connectivity with an audience into a book. My editor at Routledge was smart. He told me he didn’t want a second Gender Outlaw and that he wanted me to make the new book perform. So how do you make a book perform? How do you get somebody to want to play? I love the interactivity of the Web, but very few people take the effort to make it gentle, to tell the reader, “Honey, it’s okay. You can go here. You can go anywhere.” So I wanted to make the book gentle, and I decided to do it as a kid’s workbook. If you take away the category “man” or “woman” from a person, the only other thing most of them have been is a child.

One of the things that I like about it is that it’s a slow-release time bomb. You start out gently, but the questions that you gradually ask have considerable impact.

Which ones got you?

The gender pyramid, for one. Most people, I’d guess, are probably used to thinking of gender as male and female. A few enlightened people will also incorporate transgenderism. But what you outline is a much more detailed look at the discourse of power.

Everybody’s known for years that gender and power are linked, but given an either/or metaphor, obviously one gender would have more power over the other. But let’s look at the hierarchy and see how power affects age, class, ehtnic type, body type—let’s link all these together and see if we can get a movement started for what we’re all really talking about anyway, which is universal rights and love.

And rather than thinking of gender as being an identity that one has, you suggest that it’s a set of values that you live or enact.

You did some serious thinking about this, didn’t you?

Well, you do plug into a lot of the deeper spiritual and philosophical ramifications of gender. The material’s there.

I’m a firm believer in the Zen phrase “that which you are seeking is causing you to see.” The very fact that you see this stuff in the book is that you’re already living it, and I’d be interested in hearing how you’re living it. This shouldn’t all be about me. This is my “farewell to gender theory” book. I’m not going to be talking about this stuff anymore. I want more voices in the discourse. So go for it.

Basically, the things that attracted to me to the book were the parts about going beyond simply having an identity and actually making a life for yourself. And the very Zen-like quality of “To live a life without gender, look for where it is, and then go someplace else.”

If all you ever get out of the workbook is that phrase, and you really get it, you don’t need the workbook.

And we could substitute any number of things for “gender.” Race. Class. All of these things can be forms of oppression.

How has gender oppressed you, if I’m not prying?

As a white male, nominally or passably straight, I’d say that there are a number of expectations, both positive and negative, others have about how I think and behave.

Let’s take a look at that. Everybody likes to pin everything down on white male patriarchy, as if all white males were the same gender, and I hear a lot of resentment from white males on that. Having been a white male myself once (or passed for one, since I’m Jewish, but that’s a whole other story), I can understand that resentment. I never felt that I was part of the patriarchy others were talking about, but I had to own my complicity in that and the ways I really did behave. But let’s get back to you. What class are you?

I think of myself as middle-class, even though I’m making a working-class salary.

Let’s look at that globally, though. You’re a citizen of the United States of America, and that puts you more in the position of privileged oppressor than your being a white male. And globally, you’re living in a world of luxury. You’ve got electricity. You’ve got indoor plumbing. You’re on the telephone talking to me. That’s much more important than the fact that you’ve got a dick and you’re white. We all need to own up to the scummy things that we’ve become, whether we’ve got a vagina or a dick, if we’re middle class whites.

So what does passably straight mean?

I consider my sexual identity as “non-static”, but I don’t make an issue of it.

As children, we all learned how to pass. We learned how to not make people laugh at us, how not to get beat up. We never learned that when we grow up that we don’t have to pass. The younger generation that I’ve seen isn’t doing that. There’s more willingness to stretch what it means to be a boy or a girl or a man or a woman. Look what you’re doing; you’re talking about this stuff on the web. When I was your age, we wouldn’t do that. Look at your courage, and don’t talk to me about the fact that you pass a little.

Who we fuck is much less a part of who’s queer and who’s straight than our transgressive values. I’ve lived in the lesbian community, and dykes have been great. I’ve gotten a lot of courage from them. They’re pioneers, a real cool gender. And I’m out in the wide world now, without strong dyke arms around me, and I’ve met some really cool queer het people. By the same token, there are straight lesbians and straight gay men, the people who just want to invest in their portfolios. And I just don’t understand those people. The queer people are the ones with the transgressive values, the ones who don’t just want to save the whales, but who do something about it, the ones out there helping kids, who get involved in neighborhood activity groups, who just need to start owning another form of oppression, gender, and put it into the work that they’re already doing.

For you, it’s not about actual bashing. For me, it is. I walk through the streets of New York these days and somehow after twelve years, I’ve gotten to a point where people think I’m really pretty. If they knew what the fuck I was, I’d be a grease smear on the pavement. Where does that place me on the pyramid? Higher than somebody who looks like a guy in a dress, sure. I spent eight years looking like that. Now I don’t, and that puts me in a position of privilege.

But I have to stand up for guys in dresses and butch dykes, to claim them as family. You’re a little bit higher on the pyramid. Are you going to own me as family? If we start doing that, what a better world this would be. I know that gets sappy, and runs the risk of being New Age-y, but it’s beautiful.

But what we have to learn in embracing everyone as family is that we also have to embrace those who are higher up the pyramid than us as well.

“Please don’t make me feel any more guilty than I already feel,” right?

OK, maybe a little, but also about the recognition that, say, a white male is capable of being a sincere feminist.

I’ll let you own that, and I own that, too. It took a long time for me to understand that white males could be cool, too. I’m going to get in trouble with a lot of gay, lesbian, and trannie activists for embracing straights; I already have. But I’ll go out on a limb with you. It’s not all white male patriarchy. But most white males are on a socially propelled treadmill trying to live up to the gender ideal.

Bringing the conversation back to you and the book, what you’ve been saying about embracing everyone as family fits into what you write about the “quiet revolution” of living out this gender awareness every day.

I’m just trying to say that however you transgress, just keep doing a little more of it every day. You don’t ever have to get caught; you can stay in the closet if you want. But just keep doing it.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.